Early Days of Tennessee

Tennessee became the 13th state in the union, having previously been considered as part of North Carolina. This state has a long history of unions and labor movements fighting for workers rights. These unions are made of workers who negotiate for better pay, safety and industry standards with collective bargaining which can take the form of meetings, petitions, and eventually strikes.

Unions can span the entire US, regions, or single states. With these sizes unions are divided into locals, which are smaller groups that organize, represent, and speak for workers on a smaller scale within their area and immediate workplace. Many are craft unions, requiring specific skills such as plumbers or electrician, while others are industry unions which span multiple skill sets and areas within industries such as mining or automotive.

While unions are one of the more common ways for workers to organize associations, coalitions and other forms of organization have existed in America ever since the first settlements began to grow.

Unions as we know them took years to form, but the ideas behind them such as mutual aid, better conditions and benefits for workers are timeless ideals that have led workers to organize time and again. Workers in Tennessee found issue in low wages, long hours and would strike, a way of collectively refusing labor, or boycott, refusing to buy goods or services from the company to make themselves heard.

First Unions

collection of samples for customers to choose from (1870-1920) Barnharts Stock Cut Catalogue, pages 26-27, Library of Congress

Typographical Society

In 1836 Nashville’s Typographical Society joined the National Typographical Society (later the International Typographical Union and now the Communications Workers of America) by submitting its constitution and pricing in order to gain representation at conventions. They had thirty-five members at the time of joining. These members worked as print makers, in newspapers or book presses designing the layout, size and spacing of the words. This was one of the first official labor organizations in Tennessee. These societies helped lessen the pressure of competition amongst typographers, as well as holding them to a degree of accountability in their profession as well as their standing in society. While these societies didn’t function under the same principles of unions they were a major component of these tradesmen’s ability to maintain proper payrates for themselves, receive benefits decided on by vote, as well as upkeeping respectable appearances.

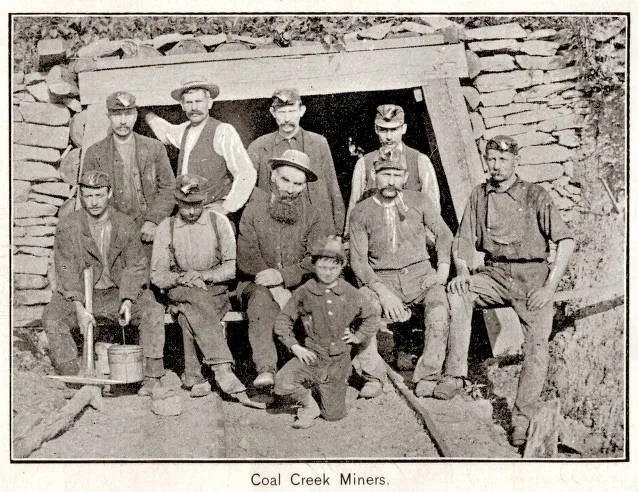

Prison labor has been a point of contention in Tennessee and America overall since the beginning. The leasing of prisoners to private companies in Tennessee began in 1866. While not a new idea, being replaced by prison labor was a slap in the face to the miners living in Coal Creek and surrounding areas.

These miners had petitioned to “incorporate a trade organization of a benevolent and charitable character” in Sept1873 and granted the ability in December. The organization was called the Miners Mechanics and Laborers Benevolent Association of Tennessee. Any mutual aid they had was helpful during these days as most miners in these towns got paid a majority of wages in scrips, a “credit” from the company for use at their stores that would only be worth about half as much at another store if they took it at all. Some towns had multiple companies operating and multiple scrips in circulation. By the 1890s workers held large grievances, such as being denied their lawful right to a third party “checkweighman” -a third party official who weighs and accounts for how much each man should be paid for- and instead being made to trust the coal company for that information. The last straw was being asked to sign contracts waiving their right to the checkweighman but also to cash payments or joining unions.

In 1891 they began their strike. After months of no movement the company decided to bring in prisoners to break the strike. Sign the agreement or lose any potential job to convict laborers. On July 14th, 300 armed miners stormed the barracks where the prisoners slept, watched by guards and officers. They rounded everyone up and marched them to a train headed for Knoxville. The guards put up no fight knowing they were out numbered and that many of the miners were previously Union and Confederate soldiers. These actions were repeated as well as other demonstrations for 2 years, bringing the attention of the governor and intervention from the national guard.

In 1893 the Tennessee government had decided that the money put into supporting and enforcing the coal companies use of prison labor was outweighing the amount made from the leases. With this in mind they signed into affect that a new prison would be built in east Tennessee to absorb the excess prisoners from Nashville to work in state owned mines and officially end convict leasing within the state in 1886.

Coal Creek Miners

Scenes of Prison Life in the South by John Durkin, TeVA

Coal Creek Miners "Souvenir of Company C, First Regiment, N.G.S.T., 1893" TeVA

Turn of the Century

This new century brought about new labor regulations and higher safety standards through state legislation and a growth of unions and workers education. with the growth of the AFL, American Federation of Labor, founded in part by the Typographical society Tennessee was seeing a boom in union participation.

1903- mines get safety standards and government officials begin routine inspections for safety.

1919- workers compensation was enacted under an elective system; employers could decide whether or not to be a part of the system by filing an exemption and all covered injuries must be accidental.

1923- made the system cover more businesses, specifically requiring coal mines to join the states system or the “Coal Operators Protective Fund”.

Myles Horton, founder of Highlander Folk School, was born 1905 in West Tennessee. As he furthered his education and worked in children’s and adult education at Church he was drawn into socialist circles. furthering his education in New York and Chicago led him to communist ideology, though he himself never joined the party having differing ideals and goals. In Chicago he encountered a Danish form of education and traveled to Denmark to see for himself. While there he began to make plans to form a school integrating ideas of his own with those of these Danish schools.

Horton moved back to Tennessee, acquiring land near Monteagle and began his school in 1932 in the midst of the Great Depression. His school focused on teaching budding leaders to interpret contracts, present grievances and organize people within the workplace. The schools techniques built on ones he learned in Denmark, encouraging students to learn from one another, create and uphold clear moral and philosophical ideals and the use of song in teaching, organizing and group building. Democratic ideals were baked into the schools culture, with the idea that all who attended were able to full partake in the community culture, freedom of thought, and equal access to livelihoods, education and health. These ideals shaped Highlander’s policy as they accepted students of any race into desegregated classes. While interest in these policies and ideals brought funding from the likes of the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, it also brought on suspicions from the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) about “subversive practices” which were dismissed and Highlander was left to continue its work with local and national unions as well as community members.

Highlander Folk School: the beginning

Oak Ridge and the War for workers rights

Oak Ridge, a city born in secrecy and need, was almost doomed from the start on the labor front. Oak Ridge was built from the ground up where there had been no existing structures for the sole purpose of the Manhattan Project, the creation and production of the atomic bomb. Arguments were made as to whether or not any unions should be allowed within the town or on any of the work sites. The Wagner Act-signed in 1935- codified citizens rights to unionize, but union meetings endangered the security and success of the Project. In the end the officials decided that construction workers could unionize -many were coming from unionized companies- but production workers could not. Workers rights stopped at the factory doors. General Grove, the man in charge of the project, reasoned that the construction workers wouldn’t see or interact with anything that could jeopardize their success. With this he was able to get the War Department as well as national union collectives such as the AFL and CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) to agree to not to start, recognize initiate any unions at Oak Ridge.

Print of Highlander Student Choir with Zilphia Horton Directing, TeVA

He Does Something About His Convictions!, Sara Sprott Morrow TeVA

Clinton Laboratories, also known as X-10 and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, TeVA

This ban on unions wasn’t the only anti-labor policy in place. Workers were barred from talking about wages, hours, benefits or anything that had to do with their positions in production. This was enforced through propaganda calling those who brought it up unpatriotic as well as informants listening in throughout the town and facilities. Any one caught breaking these rules would be fired and evicted as the US government owned all housing, supermarkets, drugstores and other commercial businesses in the town.

While the AFL and CIO had signed anti-strike agreements for the duration of the war as well as agreeing to ignore union recognition requests from Oak Ridge this did not stop workers who had come from unions, such as electricians from trying or from staging walkouts. Skilled tradesmen such as plumbers were more likely to strike or walk out in order to gain better work conditions. Their requests focused on their rights as citizens instead of their rights as workers. This was to better play into the patriotic ideals of the town and management.

After the War

Following the War Tennessee saw a boom in factory and industrial work. Jobs and union memberships were growing. However the Taft- Hartley Act slowed the growth of unions. It implemented the “right to work”, unions could no longer make employers only hire members, or force people to join. Some could make an agreement with the employer that new employees could be made to join the union after 30 days on the job otherwise it would be at their own discretion.

“View looking east from State Capitol” TeVA

Highlander Folk School’s founding ideals made the switch to focusing on Civil Rights a natural progression. The desegregated nature of the school made popularity in the wider south hard to obtain and with the refusal to denounce communist ideals following the Taft-Hartley Act made it fall out of favor with major union organizations who helped supply most of the students. Highlander continued to work with unions until the late 1950s when they began training Civil Rights leaders chosen by their peer for the same reasoning as the unions. The shaping of classes and topics followed the same outline as the unions, students were to decide on how they learn and what they were to work on for the day. Students were then given the space and tools by teachers to learn, teach, and lead their peers using personal experience and knowledge. During the transition union students would often grapple with the how and why of desegregation in the workforce. In one workshop it was decided that a clear and unwavering stance must be taken by leadership against segregation propped up by moral connections in the community as well as supporting facts from both black and white workers who have reaped benefits from desegregating.

Photograph of class attendees at Highlander Folk School library, TeVA, (Rosa Parks seated in second row)

Highlanders switch

"AFL-CIO supporters of striking Memphis sanitation workers, 1968" University of Memphis Digital Commons. 1968.

Memphis Sanitation

In 1968 two sanitation workers died due to faulty equipment, this tragedy spurred the workers to begin a strike on February 11th based on 3 grievances, safer working conditions, better pay and recognition of the union. The Memphis sanitation workers had unionized and gained support and recognition from the AFSCME (American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees) in 1964 but the Mayor, Henry Loeb, refused any official recognition for the union as well as refusing to take worn out garbage trucks out of service or pay overtime. As part of the strike workers went door to door around the city and asked residents for their support by not letting anyone else collect their trash until the end of the strike. These actioned angered Loeb who said the strike wasn’t a matter of workers rights but of public health and safety but also brought support from Martin Luther King Jr. and the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Dr. King advised leaders and came from Washington D.C. to lead peaceful protests. The first, held on March 28th erupted in violence from the back of the group with local leaders calling it off and corralling the protesters back to where they started and MLK being escorted to a local hotel before leaving. Mayor Loeb called for Marshall Law as those who incited the violence looted stores and businesses. The sanitation workers marched daily until King returned to give his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” speech on April 3rd, killed by a gunshot in his hotel room later that night prompting the mayor to institute a curfew for the city. This event lead to the strike garnering more attention and President Johnson himself putting pressure on the city to concede the demands of the union. Negotiations finally came to an end on April 16th with the city council agreeing to better pay and union recognition.